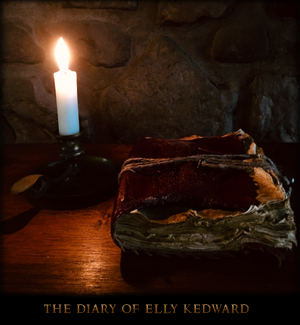

Season One begins the actual entries of Eilis Abaigeal Kedward's diary, or as she was commonly known - Elly Kedward. To better understand the context, it is imperative to read "Found Amongst the Papers of the Late William Barnes." which explains in detail how this all came into being and how we are able to share this material. Chapter One is quite revealing, in that it is taken and translated directly from her journal and now presented with proof-of-concept visuals and aural narration to better understand and appreciate her life experience, and in this case as a young girl.

She is the epitome of joy, youth, laughter and wonder. The young girl intentionally falls over and joyfully rolls down a small hill in contagious enthusiasm, coming to a stop surrounded by "all the love and gifts that nature can provide." We are finally introduced to Elly Kedward. Or rather, Elly Kedward introduces herself. Taken straight from the first page of her diary... "Is e mo ainm Elly. Elly Kedward. Rugadh me i nGleann Garbh, Eire an 21 Deireadh Fomhair i mbliana ar dTiarna 1729." Translated from Gaelic to English... "My name is Elly. Elly Kedward. I was born in Glengarriff, Ireland on the 21st of October in the year of our Lord 1729." From there, Elly shares all of the lovely aspects of her childhood. We learn that she was raised Catholic and how every day she prayed. She shares with us all about her family, of her mother and father, of the love from and for her mother and father, and of her brother whom she played with (and teased) throughout the days and nights of a wonderful childhood. She then explains of her being at her happiest when playing alone, "gan ach na hein agus na feileacain agus Dia" (with only the birds and butterflies and God as her company). Elly pretends and fancies she is a knight, not a princess, but rather a knight, leading "arm a tog me fein deanta as batai agus sreangain" (an army I've built myself made out of sticks and twine) that she creates as dolls to play with as "companions agus cosantoiri i gcoinne ainmhithe an domhain" (companions and protectors against the beasts of the world), from whence they can "a chosaint agus a ionsai na cinn olc agus olc" (defend and attack the evil and wicked ones). The protectors are simple primitive stick figures, each with a kilt, with one having a little sword she makes of a twig and attaches with a twine-made belt. The evil stick figures are quite ugly and rough, with arms and legs wrapped in weeds and dead grass. They are a strong contrast to the well-manicured stick figures of her personal army. As mentioned, little Elly is the epitome of joy, youth, laughter and wonder. We then learn those are her fantasies only, an alter-ego she has created in her own imagination, the exact opposite of her reality and of how she sees herself. In her imagination and fantasies, she is that "cailin beag gleoite beag" (pretty little blonde freckled girl) with a family, a home, a vast farm in which she can play, dance and be amongst the Lord Himself. In her reality, she is an orphan, trapped in an institution long since birth; an orphanage infested in filth, neglect, disease, abuse, rape and death. Elly is not that "pretty little blonde freckled girl," rather as she sees herself - "dilleacht breagach, breoite le gruaig dorcha, maisithe saibhir riamh a fuar i gceart agus nach raibh peire eadai ur aige riamh ... riamh" (a filthy, sickly orphan with dark, foul matted hair who has never bathed properly and hadn't a fresh pair of clothes, ever). She's worn the "feistis tattered ceanna" (same tattered dressing) for years that is rarely laundered, if ever there has been access to bathe, which is rare, very rare. She sees herself as a "carn siuil de flesh rothlach a itheann scraps agus an coirce no pratai o am go cheile" (walking pile of rotting flesh that eats scraps and the occasional oats or potato). She's never had meat, she's "Nior aimsiodh glasrai ceart riamh, no ceann amhain ar a laghad le dath" (never seen a proper vegetable, or at least one with colour). But Elly does have her fantasies. They are her only possession, and the only possession she can control; fantasies so vivid that they penetrate her subconscious to create dreams when she sleeps, to oblige her what otherwise does not exist, giving her a life she imagines by day, and then experiences in her dreams at night, as though they were real. Her dysfunctional life becomes so acute that slowly her conscious fantasies no longer deliver subconscious pleasant dreams. She is still the "pretty little freckled blonde girl" that she invented of herself, but now that fictional alter-ego too suffers from horrific torment. But she also has, and most sacred and important of all: God. Whether as a defense mechanism and/or the petrifying thought, there is nothing more than what her life has been and condemned to be. He is her hope, and she is desperate to be with Him. So despite her despondence, Elly still prays. She's convinced she's being "tastail agus triail" (tested and tried), and that the more she prays, the more "Beannaigh Dia liom le a ghrasta agus a chuid eolais" (God will bless me with His grace and knowledge). Elly is being challenged at every turn, but despite "na trialacha agus na triobloidi uile" (all the trials and tribulations), she will hold her faith to maintain her own sanity. What Elly does not know at this time is that she will one day begin a diary, a journal of her life, of where she came from, where she is, and where she hopes to be. She will call it "Deuchainn de Eilis Kedward." Translated to English... "The Trial of Elly Kedward."

Rinne me laimhseail orm, ach nior tugadh teagmhail lei riamh. Ni chuala me riamh na focail "Is brea liom tu." Nior roinntear riamh na focail "Is brea liom tu." Cailini de mo aois, cuirt siad, ansin posadh, agus iomproidh siad leanai. Ni raibh mo bhroinn ar bith i bhfad nios giorra, ach ni raibh imreoir amhain i ndiaidh a cheile. Translated to English... I have been handled, but never have I been touched. I have never heard the words "I love you." I have never shared the words "I love you." Girls of my age; they court, then marry, and bear children. My womb has been nothing short of a wicket, a wicket bowled by one player after another. Thus begins Chapter Two, Elly obviously writes this at an older age than we've known her so far. But what she's explaining is reflecting upon her childhood, that being an orphan since birth, she has only known abuse, she has only known hunger, that she has only known pain. What follows from there is a constant series of isolation, desolation and desperation. When Elly escaped the abuse of foster care, she fled to Skibbereen, unfortunately to discover corruption, filth and crime. Only a few days in, Elly is attacked and trapped by a pack of young, homeless bullies who proceed to steal the only clothes she owned, the very clothes she had been wearing. She was then arrested, assumed and accused a child prostitute, as found dirty and naked in the streets of the city. She was then incarcerated in a prison "amongst thieves, drunks, rapists, whores and murderers." Of the lifetime of the abuse and neglect, at only the age of ten, she cries that "nior mhothaigh se nach raibh me ach leanbh. Mhothaigh se nach raibh me ach cailin og. Mhothaigh se nach raibh iospartach orm. Chun an tsochai, ni raibh me ar bith nios mo na breagach." Translated to English... "It mattered not that I was just a child. It mattered not that I was just a young girl. It mattered not that I was actually a victim. To society, I was nothing more than a whore."

Dreams... ...Reality. ...Dreams of reality. ...Reality of dreams. It is now difficult to distinguish between the difference. Nil mo chomhairle ach ann i mo aisling. Nil mo shabhailteacht ann ach i mo chuid fantasies. Is i an da cheile a bhraitheann me sabhailte. Ta se nuair a dhispeasann me go bhfuil se ag brath ar a cheile. Agus is e sin nuair a thagann fantasies as nightmares. Translated to English... "My counsel has only existed in my dreams. My safety has only existed in my fantasies. It is when the two combine that I feel safe. It is when I wake that it dissipates. And it is then when my fantasies become nightmares." Elly is a devout Catholic. Considering her abusive past, and little exposure to religion at all, this alone is remarkable. But it is her appeal to God that keeps her sane throughout a constant traumatic life, even at this young age. So it's not so much as being a "Catholic," even Elly conceded that she didn't actually know what that meant at that young age, but she did know who God was. And it was her staunch faith that kept her faculties all the while. Having no resource to worship in a church, Elly dreams of her faith, actually confessing sins to a priest, sometimes multiple times a day, and comes up with confessions of sins she simply makes up, in order to ask God's forgiveness and feel His protection. The worse her traumas become the more she dreams of confession and of sins she did not commit. She just doesn't want communion, she wants the chalice filled to the rim, she wants it all. But soon her dreams "buailte chun bheith ina n-oiche chun nach feidir ealu" (conquered to become nightmares to allow no escape) from her troubles. "Ceard a bhi amhrain na n-ean thainig chun cinn de thunder" (What were songs of birds became ceaseless claps of thunder). "Bhi me a thradail, a dhiol, a phairt agus ag dul timpeall an oiread le dilleacht, bhi mo chuid ag teitheadh go dti an Sciobairin ina bhriseadh o mhalartu daonna, ag cuimhneamh ar an bpointeanas fad an tsaoil." (I had been traded, sold, bartered and passed around so much as an orphan, my fleeing to Skibbereen was a respite from human exchange, mind for the penitentiary all the while). "Ach ar an meid ata me ag ioc as a bpinsin?" (But for what am I paying penance?) She sleeps at night on dreams of being that "pretty little freckled blonde girl," with each night often with another foster family she's bartered or sold to, with only the clothes on her back and never a home she could call her own. Her only possessions now were "searbh, fearg, bron agus fury." (Bitterness, anger, resentment and fury). Elly would begin to question her faith, and demand to see a priest, to which would go ignored. To add insult to injury, this all occurred on the cusp of the Great Frost of 1741, a year that would become known as "The Year of the Slaughter."

"Bliadhain an air." Gaelic for "The Year of the Slaughter." The Season One Afterword is not taken from the words of Elly Kedward, rather displays the the environment of her life that follows immediately after Chapter Three, working as an "in-between" if you will prior to the launch of Season Two, which too will include an Afterword. During 1739 a great volcanic eruption on the remote Kamchatka peninsula in Russia, pumped thousands of tons of smoke, dust and ash into the upper atmosphere. Most Irish people at the time would have been unaware of this occurrence and if they were, they would not have known that it may have been responsible for the dramatic climate changes in Ireland and Europe for twenty-one months between December, 1739 and September, 1741. Up to this time the people in Ireland had probably become complacent about the power of extreme weather conditions to upset normal life because the winters for the previous thirty years had been relatively benign. It all began with an extremely violent storm which blew in from the east on the 29th and 30th December, 1739 bringing with it a most penetrating cold. The winds lasted for less than a week, but the terrible cold intensified during the course of January 1740, though hardly any snow fell. The first visible signs were the almost immediate freezing over of the lakes and rivers in the country. The Liffey, the Slaney, the Boyne and sections of the Shannon were frozen within days as were all the lakes, including Lough Neagh. Rivers and lakes in England were also frozen. Some people were delighted at first by the novelty of it all and carnivals and banquets on ice were held at many venues across Ireland where there was music and dancing. Some of the gentry in North Tipperary roasted a sheep on top of nineteen inches of ice on the Shannon near Portumna and later organized a hurling match on the ice between two local teams. Other people used the frozen lakes as welcome shortcuts, sometimes with fatal consequences, a funeral ran into trouble when a thin patch of ice was being crossed and twenty mourners were drowned. The all-pervasive cold had immediate effects on everyday life, most notably on people trying to stave off hypothermia. Country people who had turf stored for the winter fared better than town people but the necessity to keep the fires high saw supplies running out much earlier than usual. Coal was not available in the towns and fuel was collected where possible with trees cut down and hedges soon stripped bare. Food scarcity rapidly became a problem as the frozen rivers could not turn the waterwheels, and mills were unable to grind oats and wheat. Tens of thousands of small farmers and laboring families across the country had to come to terms with the sudden loss of their principal winter foodstuff, the potato. The fully grown potatoes left in gardens and fields where they had grown had all perished in the ground leaving nothing to eat and no seeds for potatoes. A run of relatively mild winters during the previous decade had lulled people into a sense of false security regarding their food supply and they had neglected to lay up sufficient provisions either for their families or cattle. Ireland was in the grip of the frost for almost seven weeks. It ended in late February but this unfortunately did not ease the situation. The spring had not brought rain and the severe cold north winds persisted. By April, the country had a parched look as nothing was growing. There were no sign of wildlife as the cold had killed off the birds and other small animals. Crops of wheat and barley planted the previous Autumn had failed and grass and other fodder for farm animals was non-existent. Cattle and sheep were dying the length and breadth of the country from starvation. The one and only compensation during this bleak time was that turf was saved, drawn home and stacked by April which was not known to have happened before. Still no rain fell and the terrible drought and cold continued with heavy snow falling everywhere at the start of May. The price of wheat doubled and by mid-summer 1740 the country was in a horrible social crisis. The weather meanwhile, continued to behave strangely. There had been a violent storm at the beginning of August, followed by a very windy September. Blizzards swept along the east coast at the end of October and there were massive falls of snow across most of the country in the following weeks. There were at least two storms during the month of November followed by rain, snow and frost and a downpour on the of 9th December culminating in widespread floods. A day after the floods, the temperatures dropped massively. A frost very similar to the Great Frost set in, only this time it was accompanied by a huge fall of snow which was two feet deep in places. Again rivers and lakes in Ireland and England were frozen over. On this occasion however the intense cold only lasted ten days and was broken by yet another storm as temperatures rose significantly. By December, 1740 there was full-blown famine and epidemic everywhere in the country. The poor were dying by the thousands from starvation, dysentery and typhus. The weather in the Spring and Summer of 1741 continued its strange pattern but not to the same extremes as in the previous seasons. There were violent storms in late January followed by another spring without rain. The weather in March was dry, frosty and dusty with any new grass being blasted and burned and the drought conditions lasting more or less until early July when the weather suddenly changed. The rains fell and the remainder of the summer was very hot. The harvest was fair with a reasonable crop of potatoes and a good crop of wheat. Quantities of wheat were also imported from England and America and the price of food then dropped. In early September, 1741 massive floods in Leinster caused huge structural damage but that was the finale of the weather extremes and some people saw it as the purging of the fever at the end of the famine. There was no longer a food crisis and so ended the time of the Great Frost. Over 310,000 died of starvation, fever and plague out of a population of 2 and a half million. The famine of 1845 through 1851 needs no introduction but the famine of 1740 and 1741 was more intense and proportionately more deadly. The time of the Great Frost remains to this day the longest period of extreme cold in modern European history. |

In this opening chapter of her diary, we are first met with a pretty, young, blonde girl. She is not but ten-years old, running in fields, skipping and splashing in creeks and dancing among the meadows and wildflowers of her Irish countryside.

In this opening chapter of her diary, we are first met with a pretty, young, blonde girl. She is not but ten-years old, running in fields, skipping and splashing in creeks and dancing among the meadows and wildflowers of her Irish countryside.